We Can’t Change Us, until Us Changes We

Some thoughts on learning lessons and broken feedback loops

1.

My exasperation with the Covid-19 pandemic waxes and wanes. It is always there, palpable, though at times it subsides into the relief of small victories, green shoots, the light at the end of the tunnel that may not be an approaching train after all. Or is it… ? This lack of a resolution is part of what’s so vexing, so tiring. But for an event that has stretched to nearly three years, how could it be any other way? So, I accept it, settle in for whatever comes, steel myself for the long haul, find my Zen, only to once again have all that calming breath knocked out of me by the next gut punch of flagrant stupidity. More often than not, that moment comes not from the pandemic response, but from some collective failure in our response. So naturally, I found myself nodding along in agreement with much of this piece by Jeff Maurer.

You should read the piece for yourself, but in summary, I take Maurer’s main point to be that the Coronavirus pandemic was a natural opportunity to hit pause on our brain-dead political and media culture and come together against a common obstacle. We didn’t, which is testament to our inability to act collectively and a really bad sign for our response to future challenges.

Maurer is right, but there’s something incomplete about his view. We absolutely have the ability to act collectively; it’s just that we so often insist on using it in the wrong ways. And as much as I agree with the specifics of the piece, I can’t help but think, “speak for yourself. I learned a lot from Covid.”

I learned that public health experts are informed and well-meaning but are also completely enamored with their own expertise and primarily concerned with their own status. In fact, our bureaucracy is writ large far more incompetent than I’d feared.

I learned that an awful lot of people place way too much value on partisan signaling relative to common sense or even to their own health and welfare. There’s no reason why having strong opinions on masks or vaccines or shutdowns should be so highly correlated with political opinions. This is especially stupid when you remember that initial responses to Covid were reversed.

I learned that there are very few emergencies that could get our politics back on track. A big war is could be enough, but even there I am skeptical. Unless Paul Krugman’s aliens show up, we’re going to continue to live like this for some time. Welcome to the future!

In listing all the ways that we failed, we are implicitly acknowledging that we did, in fact, learn a lot. Of course, it’s more complicated than that. I’m not here to play word games. I understand that there are two senses of the word “we,” which Maurer acknowledges from the beginning. There is the “we collectively” and “we individually”. And even if “we individually” learned plenty, the “we collectively” may be unable to implement any of those lessons. And yes, that’s a problem. In fact, I fear the problem is deeper than it looks at first blush.

2.

When de Tocqueville came to America he noted the unprecedented religious and political freedoms that (some) Americans enjoyed and also the degree to which Americans exercised their freedoms by joining associations and clubs and religious communities. This mingling of freedom and community and religiosity was somewhat paradoxical from the European perspective, where new republics were having a hard time establishing functional democratic societies without backsliding towards absolute monarchy and where the church was decidedly on the side of reaction.

This paradox of free association within a unified political order was America’s secret sauce (along with all the expropriation of land and labor), the thing that allowed us to grow into a large, well-developed economy and that gave us a political order that, while deeply flawed, was able to evolve into something better and more just. And yet, here we are today, with political partisans constantly screeching at us, demanding that we make a definitive choice between the two, insisting that any effort to bolster individual resiliency is de facto reactionary or that making investments in our collective capacity to deal with a litany of very real problems is the creeping guise of socialism. It’s enough to drive one mad, which might explain why there’s so much madness about.

I can’t help but think about Hillary Clinton, who published a book called It Takes a Village (that was perhaps based on a phony African proverb), and triggered a minor conservative backlash, an insistence that no, “it takes a family.” It was an incredibly stupid back and forth, but one that neatly illustrates the shape our current dysfunction.

I know it’s a non-sequitur, but stick with me. I am trying to answer a few questions relevant to our present predicament. For example, how exactly do you separate the importance of family and community? Are there lots of healthy, functioning communities that are composed of broken individuals and dysfunctional families? And likewise, are there a lot of high-functioning individuals thriving within crumbling communities? Individuals form families and families compose communities and the health of one is inextricably tied up with the health of the other. To view it any other way, is to declare yourself ether stupid or insane. What I’m trying to figure out is how we ended up with a political culture that demands we be either stupid or insane.

Again, I don’t wish to get hung up on word games. I get that these terms act as a cipher for a larger debate on priorities, that they’re just rallying points for the “real issues.” I also think that story is bullshit.

In reality, people tend to publicly profess the beliefs needed to stay in good standing with their political or social tribe and then privately go and do whatever it is that benefits them personally. Yes, of course it takes a village to raise a child, but we should probably notice that in Hillary’s case, the village she chose was the incorporated hamlet of Chappaqua, which Wikipedia describes thusly:

As of the census of 2010, there were 1,434 people residing in Chappaqua. According to the 2015-2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, there are 595 housing units and the median household income is $250,000+. The racial makeup of the CDP was 76.1% White alone, 0% Black or African American alone, 0% Native American alone, 22.6% Asian alone, 0% Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander alone, 0% some other race alone, and 1.3% from two or more races.

According to the 2010 census results, in the CDP, the median age was 39 years, with 3.8% of the population under 5, 81.6% 18 and older, and 10% 65 and older. Males had a median income of $207,083 versus $128,750 for females. 0% of families were below the poverty line. 6.6% of people old enough had a high school or equivalent degree of education, 5.8 had some college but no degree, 4% had an associate degree, 37.3% had a bachelor's degree, and 46.3% had a graduate or professional degree.

Nationwide, Chappaqua ranks 42nd among the 100 highest-income places in the United States (with at least 1,000 households). In 2008, CNNMoney listed Chappaqua fifth in their list of "25 top-earning towns." Chappaqua 2007 estimated median household income was $198,000.

In other words, when HRC had to decide where to settle her family after Bill left the White House, she chose a place that is every bit the stereotypical wealthy suburban enclave in which you’d expect to find the folks on the other side of that phony debate, a place that exists to give people with means the ability to withdraw and exclude those that don’t. And yes, there are a thousand examples of conservatives who talk to no end about self-sufficiency and rail against moochers and welfare queens, but then avail themselves of whatever government largesse is available to them and their base. This is a bipartisan affliction.

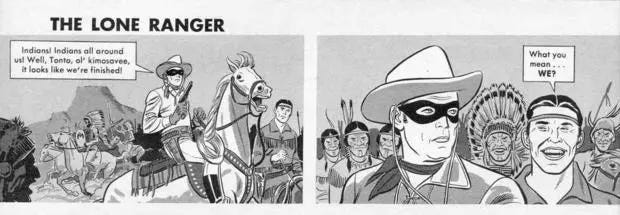

I won’t go to deep into this because these debates are very low on the signal-to-noise ratio. Plus, I can’t be too hard on Clinton. I’m never too hard on people doing their best to raise their families. I even have some grace for conservatives and their individualist settler fantasies. The myths of the American west are seductive, and as a black man, I understand the dangers of making idols out of sociopaths with guns.

3.

If I asked you to clap your hands and then demanded that you tell me whether the right hand or the left hand made the noise, you’d think I was daft. And yet, that is exactly what our contemporary politics asks us to do, to take complicated, multifaceted problems and reduce them to a flat, two-sided view. This is where the major pandemic failures are implicated, in the idea that you have to pick one thing to maximize to the exclusion of all the other things that we value.

We should be capable of having a rational discussion about the merits of shutdowns that take into account both the health impacts of the virus and the impacts to people’s livelihoods and their mental and emotional well-being. We should be able to acknowledge how the disease affects different demographics without descending into weird rants about euthanizing old people or how we don’t “care” about marginalized communities. We should be capable of understanding that facemasks are marginally helpful at reducing the amount of virus in the air, but are not magical protection shields that somehow prevent the spread of the virus when you walk in the restaurant but become unnecessary when you sit down for the meal.

We, as individuals, make these kinds of nuanced calculations every single day. And for the most part we manage our personal risks well. But when it comes to political decision-making, we start to lose our fucking minds.

What is even scarier to me personally, is that we may be losing the ability to separate the politically rational from the personally insane. This is what scares me. The “it takes a village” back and forth was mostly symbolic. Bill Clinton put his office in Harlem, but his family in Westchester. But now people are starting to take this dumb shit literally. And that won’t end well.

4.

When it comes to the case of Herman Cain, there is a temptation to make some kind of Darwin Award joke. Not only because it is unkind, but because it misses the larger point. Darwin implies evolution, which implies natural selection, which implies a mechanism that allows evolutionary fit behavior to flourish while consigning unfit behavior to the genetic waste bin. That same mechanism is what allows successful societies to grow and prosper and what forces others into rot and decay. Cain’s individual failure is notable, but the more important observation is about the political culture that enabled his failure, and not because it couldn’t come together and make decisions, but because it came together and made the wrong decisions.

This is why I say that Maurer’s piece is missing something. Our problem isn’t so much that we can’t adapt, but that we’ve begun to maladapt. We’re learning to make decisions not in accordance with survival and human flourishing, but with trying to win stupid political games. Herman Cain’s behavior was perfectly suited for what he wanted to be, a major player in Trumpworld. He chose his political standing over his own physical well-being, and I fear that this will be a feature, and not a bug, of the world that’s coming.

The point I’m trying to make is subtle. The difference between failing to adapt and maladapting is a matter of perspective, but it’s also the difference between losing ground to encroaching danger and running headlong towards it. Both can end badly, but one gets there a lot quicker.

All said, I am simultaneously hopeful and despondent. On the one hand, learning is failing. Valuable lessons don’t just fall out of trees and smack us on the head; they are usually the result of some measure of pain or discomfort, and there’s plenty of that for the taking. On the other hand, learning only happens when there is a functioning feedback loop, a way to objectively judge the consequences of our actions and make changes in response. Unfortunately, we’re steadily abandoning objective feedback loops and replacing them with overlapping systems of patronage and self-delusion. You can’t change if you’re being patronized.

I don’t believe there is a way of “fixing” our political culture. Too much of it has metastasized. The only way for things to get better is for us to stop worrying so much about how terrible everything is and start making corrections where we stand.

Just as communities are composed of households and individuals, the “we collectively” is composed of the “we individually.” The only way for the “we collectively” to change is for the “we individually” to stop waiting for the collective to get better and start changing individually. So yes, we have an unaccountable bureaucracy. Yes, we have politicians that would rather play games than solve problems. Yes, we have real difficulty in collectively processing complex thoughts. But none of that can change until enough of us simply decide to stop playing these stupid games.

The real question isn’t whether we’ve learned anything or not from the pandemic. How could we not have learned something? The real question is, “what will we do with this information?”

I disagree. On many points, but they all run back to one single issue; there is no one way to run the US. No single interpretation of the constitution, no consensus of what is more important, the individual or the collective. And this carries in its wake all of those little things that make up the greater political struggle.

Covid enabled a sharp divergence in what people felt should be the response and how society should function. How heavy should be the hand of gov't? And the problem was compounded by it being an election year in which a polarizing president was up for reelection. So, yes, there was a lot of star-bellied-sneech type stuff, but mixed in with that was more than a bit of deep and abiding personal philosophy. Much of which comes down to that same question; the needs of the one verses the needs of the many. I think we can skip the points and figures that each side marshals to prove their point re covid, it is all pretty banal at this point. But each side takes their data whole, with no room for dissent.

I am often reminded of 1968 at this point, not because I was around then (I am only 51) but due to the intense social pressures being applied across the board. It was, in many peoples view a time of change over, socially. And I feel that we are in the middle of the change back from that paradigm. The progressivism that arrived from that period is being pushed back, not just in the states, but across the board, and much of this tsuris is related to that.

This is excellent. Crisp, insightful, and to the point. Thank you for writing it.